Ethics of screening based on race/ethnicity

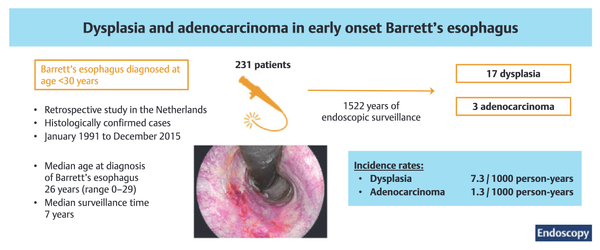

This article explores some of the ethical implications of using race and ethnicity for cancer screening, using esophageal adenocarcinoma and gastric cancer as examples. It highlights the disparities in cancer incidence and mortality among different racial and ethnic groups and examines the potential benefits and drawbacks of screening based (in part) on social constructs. The authors argue for the consideration of social determinants of health when possible, as alternatives to race-based stratification, emphasizing the need for further research to develop equitable screening practices that do not exacerbate health disparities. It is well-worth a careful read.

The Ethics of Cancer Screening Based on Race and Ethnicity.

Mülder DT, O'Mahony JF, Doubeni CA, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Schermer MHN.

Ann Intern Med. 2024 Sep;177(9):1259-1264. doi: 10.7326/M24-0377. Epub 2024 Aug 6. PMID: 39102717.

Abstract

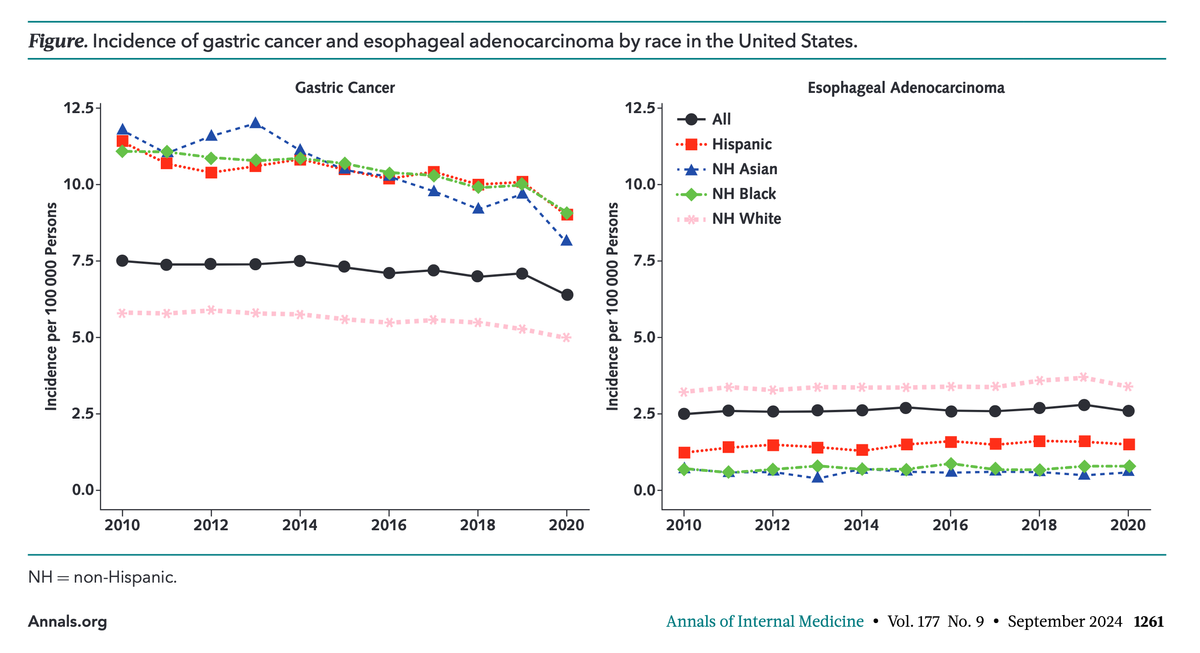

Racial and ethnic disparities in incidence and mortality are well documented for many types of cancer. As a result, there is understandable policy and clinical interest in race- and ethnicity-based clinical screening guidelines to address cancer health disparities. Despite the theoretical benefits, such proposals do not typically address associated ethical considerations. Using the examples of gastric cancer and esophageal adenocarcinoma, which have demonstrated disparities according to race and ethnicity, this article examines relevant ethical arguments in considering screening based on race and ethnicity.

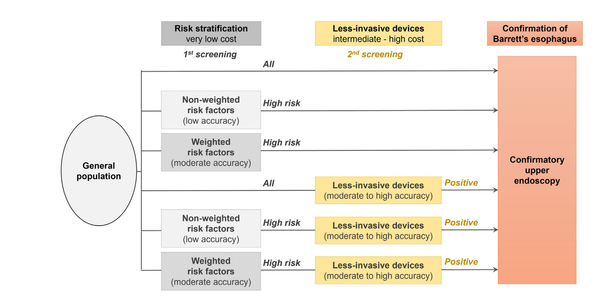

Race- and ethnicity-based clinical preventive care services have the potential to improve the balance of harms and benefits of screening. As a result, programs focused on high-risk racial or ethnic groups could offer a practical alternative to screening the general population, in which the screening yield may be too low to demonstrate sufficient effectiveness. However, designing screening according to socially based categorizations such as race or ethnicity is controversial and has the potential for intersectional stigma related to social identity or other structurally mediated environmental factors. Other ethical considerations include miscategorization, unintended negative effects on health disparities, disregard for underlying risk factors, and the psychological costs of being assigned higher risk.

Given the ethical considerations, the practical application of race and ethnicity in cancer screening is most relevant in multicultural countries if and only if alternative proxies are not available. Even in those instances, policymakers and clinicians should carefully address the ethical considerations within the historical and cultural context of the intended population. Further research on alternative proxies, such as social determinants of health and culturally based characteristics, could provide more adequate factors for risk stratification.