Risk and Protective Factors

Esophageal Adenocarcinoma

Epidemiologic and clinical research has revealed many risk factors which, taken together, can help estimate a person’s probability of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC). These include:

- demographic factors,

- host and lifestyle factors,

- medications,

- family history, and

- genetic markers.

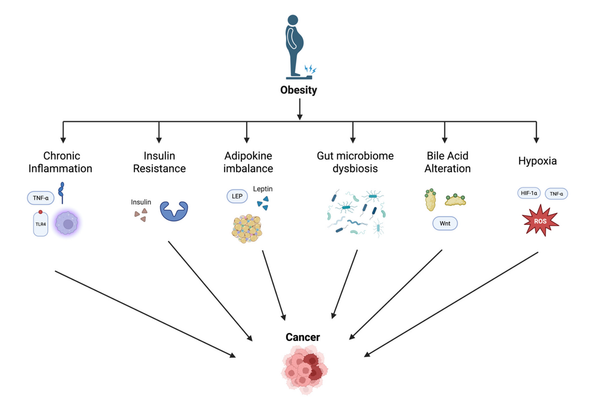

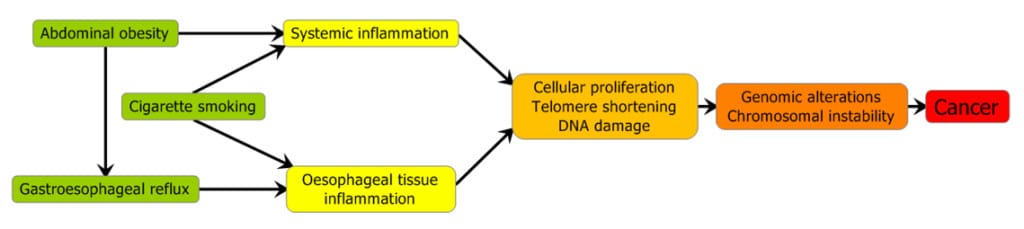

In the general population, symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux (sGERD), obesity, cigarette smoking, and family history of BE or EAC are the major factors associated with increased risk.(1–6) Conversely, physical activity, use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and statin drugs have been associated with decreased risk in observational studies and randomized clinical trials.(7–11) Many of these factors are thought to affect EAC risk through the exacerbation (or reduction) in inflammation (figure 1.)

It is important to note that while the observational studies are generally very consistent in finding the above associations, they are not necessarily causal, and no randomized clinical trials have examined the extent to which behavioral change (e.g., losing weight, quitting smoking) actually affects risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma. In contrast, a number of clinical trials have reported on reduced risk associated with statin use, although esophageal cancer was not the primary endpoint. A recent trial(11) of use of aspirin and/or a proton pump inhibitor did find a suggestion (not quite statistically significant) that aspirin might be effective, especially along with proton pump inhibitors; this finding is supported by a number of observational studies.

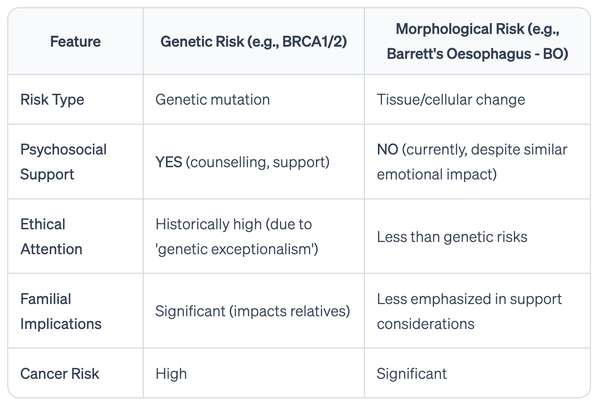

Regarding other potential risk factors, a strong body of epidemiologic evidence suggests that infection with the Helicobacter pylori bacterium is associated with an approximately 50% decreased risk of EAC although the mechanism(s) remain unclear.(12, 13) Similarly, there is some evidence from observational studies that diet, in particular higher intake of fat and lower intake of fruits and vegetables, is associated with increased EAC risk.(14, 15) Finally, while almost two dozen genetic loci have been identified as associated with EAC risk(16), as a whole, their added discriminatory ability is still rather modest, especially compared to family history.(17,18)

Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma

In the U.S., tobacco smoking and alcohol use, with a lesser contribution from a poor diet (e.g., low intake of fruit and vegetables), account for almost 90% of ESCC cases.(19) In other regions of the world, the situation is more complicated with numerous risk factors that are population-specific.(20-22)

The highest ESCC incidence rates in the world occur in Central and Eastern Asia, Eastern Africa, and Uruguay and neighboring parts of Brazil; within these broad regions, a number of well demarcated hotspots have been observed. In many, observational studies and cancer prevention trials have investigated potential underlying causes and prevention methods. One area of particular interest has been Linxian, China, where research has identified a number of factors that influence EC risk, including diet (e.g., eating pickled vegetables and low intake of fruits and vegetables), nutritional and micronutrient deficiencies, intake of hot beverages, exposure to indoor air pollutants, and poverty, along with smoking and genetics.(23) Public health efforts to reduce risk factor prevalence and increase screening and early detection have begun to lead to lower incidence and mortality rates.

Similarly, in Golestan Province in NE Iran, another high-risk area, no single risk factor has been identified, but rather a number of factors seem to be at work, including drinking hot tea and un-piped water, smoking opium, poor diet, poor oral health and exposure to indoor air pollution.(24) In other populations, betel quid chewing in the Asia-Pacific region, drinking (Yerba) mate tea in Uruguay and drinking Calvados in Northern France. High risk areas of Africa have been the focus of fewer studies, although smoking and alcohol appear to be important.(25) Recently indoor air pollution, specifically PAHs from burning wood, has been linked with precancerous esophageal lesions.(26)

Summary

EAC and ESCC are two distinct cancers with vastly different incidence and risk factor profiles. Figure 2 summarizes and contrasts many of the known and suspected risk factors for EAC and ESCC.(22)

References

1. Reid BJ, Li X, Galipeau PC, et al. Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma: time for a new synthesis. Nat Rev Cancer 2010;10:87–101.

2. Cook MB, Corley DA, Murray LJ, et al. Gastroesophageal Reflux in Relation to Adenocarcinomas of the Esophagus: A Pooled Analysis from the Barrett’s and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma Consortium (BEACON). PLoS ONE 2014;9:e103508.

3. Hoyo C, Cook MB, Kamangar F, et al. Body mass index in relation to oesophageal and oesophagogastric junction adenocarcinomas: a pooled analysis from the International BEACON Consortium. Int J Epidemiol 2012;41:1706–18.

4. Cook MB, Kamangar F, Whiteman DC, et al. Cigarette smoking and adenocarcinomas of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction: a pooled analysis from the international BEACON consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102:1344–53.

5. Sun X, Elston RC, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, et al. Predicting Barrett’s Esophagus in Families: An Esophagus Translational Research Network (BETRNet) Model Fitting Clinical Data to a Familial Paradigm. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2016;25:727–735.

6. Xie S-H, Lagergren J. Risk factors for oesophageal cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2018. Available at: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1521691818300933 [Accessed December 2, 2018].

7. Thomas T, Loke Y, Beales ILP. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis: Use of Statins Is Associated with a Reduced Incidence of Oesophageal Adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Cancer 2017.

8. Liao LM, Vaughan TL, Corley D a, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use reduces risk of adenocarcinomas of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction in a pooled analysis. Gastroenterology 2012;142:442–452.e5; quiz e22–3.

9. Moore SC, Lee I, Weiderpass E, et al. Association of leisure-time physical activity with risk of 26 types of cancer in 1.44 million adults. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:816–825.

10. Rothwell PM, Fowkes FGR, Belch JFF, et al. Effect of daily aspirin on long-term risk of death due to cancer: analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet 2011;377:31–41.

11. Jankowski JAZ, Caestecker J de, Love SB, et al. Esomeprazole and aspirin in Barrett’s oesophagus (AspECT): a randomised factorial trial. Lancet 2018;392:400–408.

12. Islami F, Kamangar F. Helicobacter pylori and esophageal cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa) 2008;1:329–338.

13. Coleman HG, Xie S-H, Lagergren J. The Epidemiology of Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(2):390–405.

14. Abnet CC, Corley DA, Freedman ND, et al. Diet and Upper Gastrointestinal Malignancies. Gastroenterology 2015;148:1234-1243.e4.

15. O’Doherty MG, Cantwell MM, Murray LJ, et al. Dietary fat and meat intakes and risk of reflux esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer 2011;129:1493–1502.

16. Contino G, Vaughan TL, Whiteman D, et al. The evolving genomic landscape of Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology 2017.

17. Dong J, Buas MF, Gharahkhani P, et al. Determining Risk of Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma Based on Epidemiologic Factors and Genetic Variants. Gastroenterology 2018;154:1273-1281.e3.

18. Kunzmann AT, Canadas Garre M, Thrift AP, et al. Information on Genetic Variants Does Not Increase Identification of Individuals at Risk of Esophageal Adenocarcinoma Compared to Clinical Risk Factors. Gastroenterology 2018.

19. Engel LS, Chow WH, Vaughan TL, Gammon MD, Risch HA, Stanford JL, et al. Population attributable risks of esophageal and gastric cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003 Sep;95(18):1404–13.

20. Abnet CC, Arnold M, Wei W-Q. Epidemiology of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2018 Jan 1;154(2):360–73.

21. Xie S-H, Lagergren J. Risk factors for oesophageal cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2018 Dec;36–37:3–8.

22. Thrift AP. Global burden and epidemiology of Barrett oesophagus and oesophageal cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2021) Feb 18.

23. Wang S-M, Abnet CC, Qiao Y-L. What have we learned from Linxian esophageal cancer etiological studies? Thorac Cancer. 2019 May;10(5):1036–42.

24. Sheikh M, Poustchi H, Pourshams A, Etemadi A, Islami F, et al. Individual and Combined Effects of Environmental Risk Factors for Esophageal Cancer Based on Results From the Golestan Cohort Study. Gastroenterology. 2019 Apr;156(5):1416–27.

25. Asombang AW, Chishinga N, Nkhoma A, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of esophageal cancer in Africa: Epidemiology, risk factors, management and outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2019 Aug 21;25(31):4512–33.

26. Mwachiro MM, Pritchett N, Calafat AM, Parker RK, Lando JO, Murphy G, et al. Indoor wood combustion, carcinogenic exposure and esophageal cancer in southwest Kenya. Environ Int. 2021 Jul;152:106485.